It can provide us with crucial clues on how the Moon came to be as it is.

Others are reading now

When NASA’s Artemis astronauts touch down near the moon’s south pole in the coming years, they may step into one of the richest scientific sites in lunar history

A new study suggests the area hides deep clues to how the moon — and perhaps the Earth itself — came to be.

The research, led by planetary scientist Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna from the University of Arizona, was published in Nature and offers fresh insight into the moon’s violent beginnings and its strikingly uneven appearance.

A colossal collision

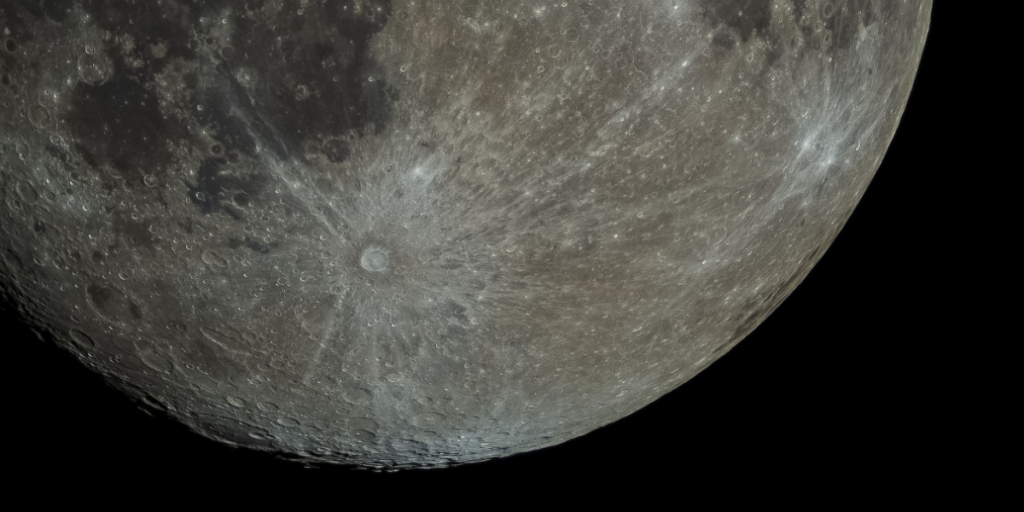

Roughly 4.3 billion years ago, a massive asteroid slammed into the far side of the moon, carving out the South Pole–Aitken basin, or SPA — the largest crater on the lunar surface.

Spanning more than 1,200 miles north to south and 1,000 miles east to west, it was created not by a direct hit but a glancing blow.

Also read

Andrews-Hanna’s team compared SPA with other giant impact basins across the solar system and discovered a consistent “teardrop” shape, narrowing in the direction the impactor traveled.

Contrary to earlier theories that the asteroid struck from the south, the new data indicates it came from the north.

“This means that the Artemis missions will be landing on the down-range rim of the basin – the best place to study the largest and oldest impact basin on the moon, where most of the ejecta, material from deep within the moon’s interior, should be piled up,” Andrews-Hanna said in an article from University of Arizona.

Secrets beneath the surface

The researchers analyzed the crater’s topography, crustal thickness, and chemical composition, finding further evidence of a northward impact.

The results also hint at how the moon’s interior evolved over billions of years.

Also read

Scientists believe the young moon was once covered by a global “magma ocean.” As it cooled, heavier minerals sank to form the mantle, while lighter ones floated to create the crust.

The last liquid layer trapped between them concentrated certain leftover elements — potassium, rare earth elements, and phosphorus — collectively called “KREEP.”

“If you’ve ever left a can of soda in the freezer,” Andrews-Hanna said, “you may have noticed that as the water becomes solid, the high fructose corn syrup resists freezing until the very end and instead becomes concentrated in the last bits of liquid. We think something similar happened on the moon with KREEP.”

Uneven by nature

KREEP elements are most abundant on the moon’s near side, which faces Earth and is marked by dark volcanic plains.

The far side, by contrast, is rough and heavily cratered. Why this imbalance exists has long baffled scientists.

Also read

According to Andrews-Hanna, the far side’s thicker crust may have forced molten rock from the early magma ocean to squeeze toward the near side — “like toothpaste being squeezed out of a tube.”

This uneven distribution likely caused the intense volcanic activity that shaped the lunar face visible from Earth.

The SPA crater provides evidence for this process. Researchers found a patch of radioactive thorium — a hallmark of KREEP-rich material — concentrated on one side of the basin.

That, they say, marks a “window” into the moon’s layered crust, where remnants of the ancient magma ocean once flowed.

Clues for Artemis explorers

The findings suggest that samples collected during upcoming Artemis missions could shed unprecedented light on the moon’s early evolution.

Also read

While spacecraft observations have mapped thorium deposits from orbit, direct analysis of lunar rocks will offer a much clearer picture.

“Those samples will be analyzed by scientists around the world, including here at the University of Arizona,” Andrews-Hanna said. “With Artemis, we’ll have samples to study here on Earth, and we will know exactly what they are.”

Researchers hope those samples may finally explain how the moon’s strange asymmetry developed — and what that story reveals about the origins of Earth’s closest neighbor.

Sources: Nature; University of Arizona; NASA