For some people, recognizing other people is not automatic but uncertain and effortful. New research sheds light on how this invisible condition shapes daily life and challenges the way it is diagnosed.

Others are reading now

A woman walks into a staff meeting and takes her usual seat. She recognises the voices around the table, the way one colleague clears his throat before speaking. But the faces themselves do not settle into place. She waits for someone to say a name before she risks addressing them.

For a small but significant minority, this is ordinary life. According to a new PhD thesis from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, even specialists are still wrestling with how face blindness should be defined and diagnosed.

A field still arguing

In his 2025 doctoral thesis, Beyond Face Value: The Phenomenology and Assessment of Developmental Prosopagnosia, psychologist Erling Nørkær looks at both lived experience and the methods used to identify the condition.

Developmental prosopagnosia, often called face blindness, is estimated to affect up to 3 percent of the population. Unlike the acquired form, which can follow a stroke or head injury, this variant appears without clear neurological damage and often goes unrecognised for years.

Researchers have long disagreed about where to draw the line between weak face memory and a diagnosable impairment.

Also read

“We have found enormous variation in how researchers classify prosopagnosia. That makes it unclear whether we are even talking about the same phenomenon across studies,” Nørkær said at the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Psychology.

Different tests. Different thresholds. It adds up to uncertainty in a field that is still trying to pin itself down.

More than definitions

But the argument over criteria is only part of it.

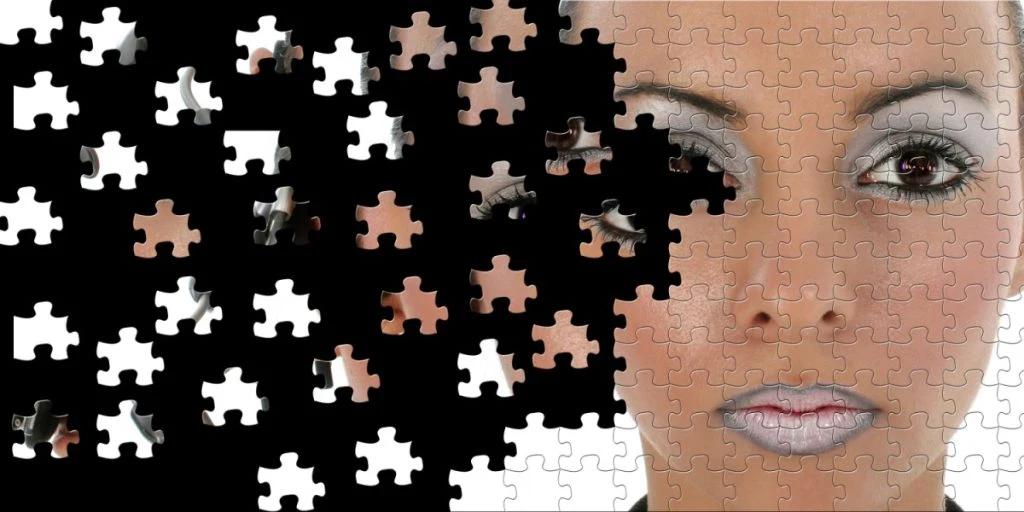

“We know that faces are central to human interaction – from the moment we are born. But for people with prosopagnosia, the face is not a shortcut to identity. It is a puzzle that has to be solved,” Nørkær said.

In interviews, participants described focusing on isolated details such as eyebrows, hairstyles or distinctive glasses, building recognition piece by piece. One office employee relied on fixed seating plans; A university student memorised coats and bags before lectures began.

Also read

“Our interviews show that face perception fluctuates between individual features – such as eyes or mouth – and a fleeting sense of the whole. What for most people is an immediate experience becomes for them a fragile construction that often falls apart,” he explained.

The social cost can be real. Misunderstandings. Awkward apologies. Avoidance.

Recognition, slowly

When recognition does happen, it tends to come late.

“Recognition does not happen at a glance, but typically only when the other person gives a social cue – a smile or a greeting. It is like putting together a puzzle where the pieces are context: voice, hair, surroundings,” Nørkær said.

Alongside the interviews, the thesis evaluates revised versions of the widely used PI20 self-report questionnaire and proposes a five-question ultra-short screening tool, intended for research and clinical use so that screening reflects how people describe their daily struggles.

Also read

“By defining what prosopagnosia is – and not only what it is not – we can develop more targeted strategies to support those who live with it,” he said.

Source: Erling Nørkær (2025), Beyond Face Value: The Phenomenology and Assessment of Developmental Prosopagnosia, PhD thesis, Department of Psychology, University of Copenhagen.