Nearly 100 years ago, a group of undergraduates at George Washington University attempted to stay awake for more than two days straight. It was part of a bold experiment to determine whether sleep was truly necessary — or just a waste of time.

Others are reading now

Nearly 100 years ago, a group of undergraduates at George Washington University attempted to stay awake for more than two days straight. It was part of a bold experiment to determine whether sleep was truly necessary — or just a waste of time.

A psychology professor questioned sleep itself

Frederick August Moss, a GWU professor and the original creator of the MCAT, believed sleep was a useless habit. In 1925, he designed an experiment to see if humans could function — even thrive — without it.

The sleepless challenge begins

In late August, Moss gathered seven students in Washington, D.C., and asked them to stay awake for 60 hours. He tested their reflexes, assigned tasks like parallel parking, and monitored their mental sharpness throughout.

Future leaders in the study group

Among the volunteers were Louise Omwake and Thelma Hunt — both of whom went on to influential careers in psychology and education. Hunt would later chair GWU’s psychology department, following in Moss’s footsteps.

Singing, baseball, and country drives to stay awake

The group passed time by driving through the Virginia countryside, playing games, and singing songs. Remarkably, all seven succeeded in staying awake for the full 60 hours.

Also read

The early verdict: sleep might be overrated

Popular Science summarized Moss’s conclusions by comparing sleep to intoxication — suggesting that “too much sleep” could dull the mind. The experiment reflected a broader 1920s fascination with productivity and efficiency.

A cultural moment of sleepless ambition

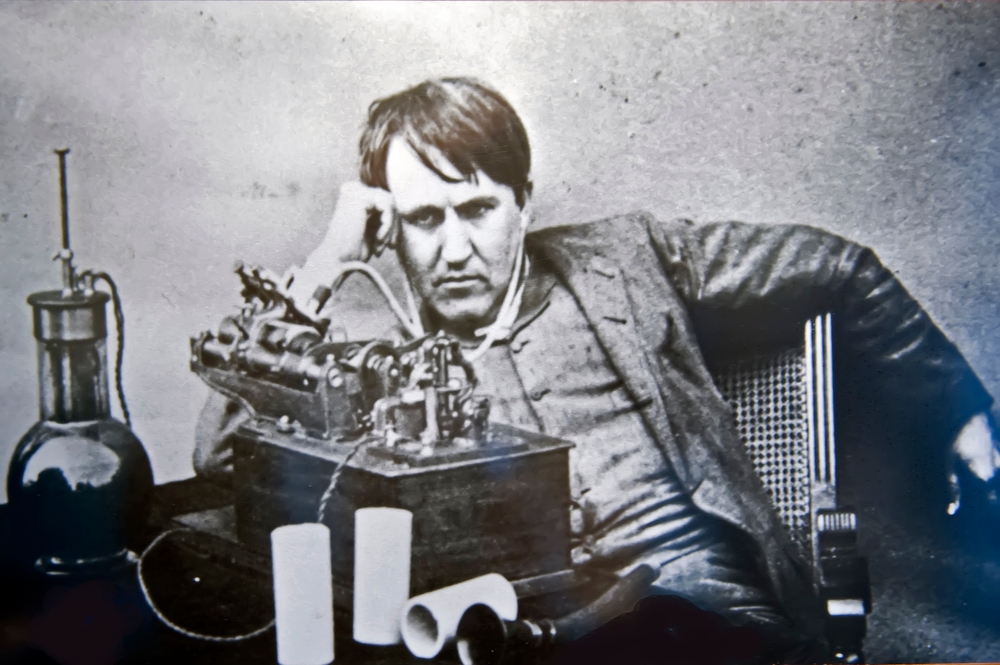

The idea that sleep was optional aligned with the spirit of the age. Inventor Thomas Edison famously claimed he needed only four hours of rest per night, and other experiments tried to prove sleep wasn’t biologically essential.

Not everyone was convinced

Science writer Newton Burke expressed skepticism, noting that similar studies — including one at the nation’s first sleep lab — showed that skipping sleep often led to health issues and cognitive decline.

A century of sleep research changes everything

Today, science confirms that sleep isn’t passive. It’s when the brain consolidates memory, clears toxins, and regulates hormones. It’s vital for immune function, metabolism, and overall well-being.

Too much sleep may also be a red flag

Modern research shows both too little and too much sleep are linked to poor health outcomes. Oversleeping may be a symptom of other conditions like depression, sleep apnea, or chronic illness.

Also read

Sleep consistency matters, too

Irregular sleep schedules — not just short sleep — are associated with higher risks of obesity, heart disease, and mood disorders. Experts emphasize routine, along with good sleep hygiene.

The legacy of 60 sleepless hours

The 1925 experiment may have been flawed, but it sparked a conversation that has lasted a century. As we continue to explore sleep’s mysteries, one thing is certain: it’s no longer seen as a waste, but a cornerstone of good health.