The Roman emperor Caligula had surprising medical knowledge.

Others are reading now

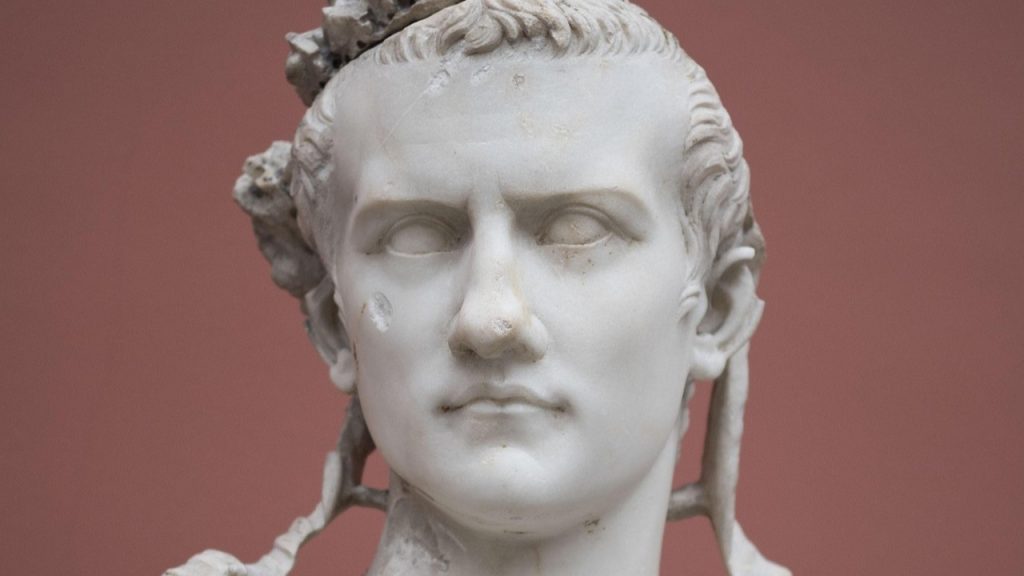

Long mocked for madness, Emperor Caligula may have had surprising medical expertise, including detailed knowledge of herbal treatments, according to new research into ancient Roman texts.

More Than Just a Tyrant?

Rome’s third emperor, Caligula, is often remembered for tales of bloodlust, paranoia, and bizarre decisions, none more infamous than supposedly appointing his horse to the Senate.

But recent scholarly work reveals another side to the emperor that history has long overlooked.

An Ancient Incident

In a new article published in Proceedings of the European Academy of Sciences & Arts, scholars Andrew J. Koh of Yale University and Trevor S. Luke of Florida State University re-examine an episode recorded by Roman historian Suetonius.

The incident involves a Roman senator who travelled to Antikyra, a Greek city famed in antiquity for its use of the herb hellebore, used in the treatment of epilepsy, melancholy, and mental disorders.

Also read

Not Just Cruelty?

When the senator requested yet another medical leave extension, Caligula ordered his execution, quipping: “A bloodletting was necessary for one whom hellebore had not benefited in all that time.”

It was long assumed this remark merely demonstrated Caligula’s cruelty. But Koh and Luke argue otherwise.

A Sinister Joke or Medical Insight?

According to the researchers, the emperor’s remark was grounded in genuine medical knowledge of his time.

The line mirrors clinical language found in Roman medical treatises, particularly Celsus’s De Medicina, a major reference in Roman-era medical practice.

Caligula’s mention of bloodletting as an alternative to hellebore suggests not just casual knowledge, but familiarity with therapeutic sequencing; the idea that if one treatment fails, another should be tried.

Also read

It may even hint that Caligula had personal experience with both remedies.

The Healing Reputation of Antikyra

To understand the full significance of Caligula’s statement, the researchers turned their attention to Antikyra, a small town that loomed large in the Roman imagination for its medical offerings.

Through ethnobotanical fieldwork and analysis of ancient texts, scholars at the Yale Ancient Pharmacology Program (YAPP) found that while pure hellebore may have been rare even in Antikyra, local healers produced complex potions combining it with sesamoides, an herb believed to mitigate hellebore’s toxicity.

“Mayo Clinic of the Roman World”

This potent mixture likely contributed to Antikyra’s reputation as a kind of “Mayo Clinic of the Roman world,” Koh told The Guardian.

Roman elites had long turned to Antikyra for treatment.

Also read

One such figure was Marcus Livius Drusus, Caligula’s great-great-grandfather, who received treatment there in 91 BCE for epilepsy, a condition that may have run in the family.

Was Caligula a Medical Tourist?

The researchers suggest that Caligula’s connection to Antikyra wasn’t incidental.

Ancient sources describe the emperor suffering from insomnia, epilepsy, and possibly mental illness — all of which were traditionally treated with hellebore.

Combined with the fact that his father Germanicus died under suspicious circumstances, possibly by poisoning, Caligula may have had strong personal reasons to study medicine, especially pharmacology.

In a politically charged environment, knowing one’s poisons and antidotes may have been less a hobby and more a necessity.

Also read

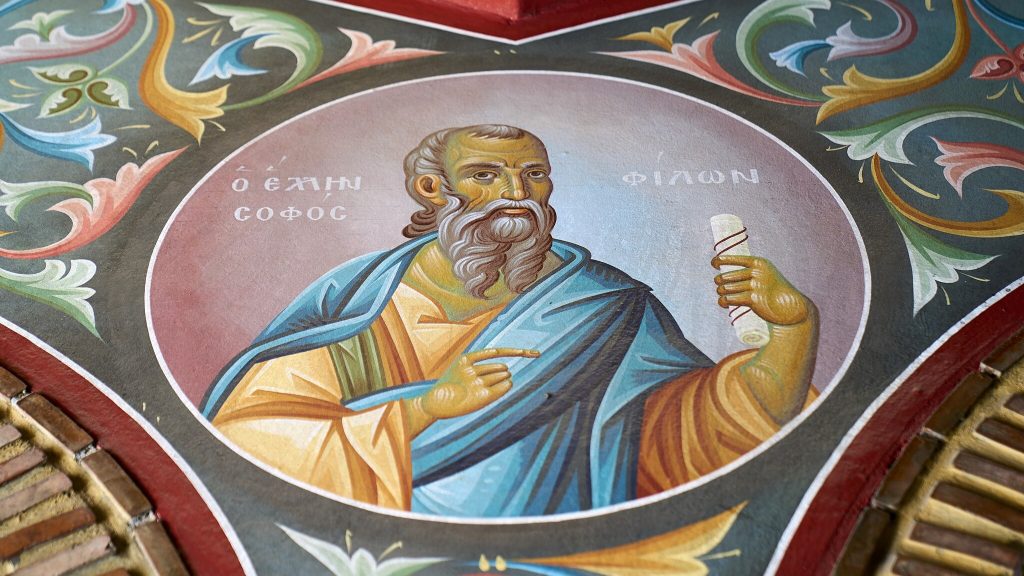

A Philosopher’s Backhanded Compliment

Even Caligula’s critics, like Philo of Alexandria, acknowledged his deep knowledge. Philo, who disapproved of Caligula’s rule, nonetheless accused him of misusing Apollo’s healing arts.

Far from being purely a figure of ridicule or terror, Caligula may have operated with a more complex grasp of the tools available to him, not just swords and fear, but syrups and salves.

Rewriting the Narrative

Koh and Luke are not on a mission to rehabilitate Caligula’s image.

His reign remains one of Rome’s most brutal and bizarre.

But by reinterpreting historical accounts with modern interdisciplinary tools, they argue we may be seeing only part of the picture.

Also read

Suetonius and other ancient biographers had agendas. What may have begun as medical insight or personal precaution might have been rewritten over time into tales of paranoia and poison, madness and murder.