For decades, families whose relatives were stripped of their collections under Nazi persecution have struggled to recover even a fraction of what was taken.

Others are reading now

Now a major change in Germany’s restitution system has triggered an outcry from claimants who say the new process will shut them out entirely.

According to reporting by The Mirror, families and experts believe the rules introduced this week risk protecting museums rather than survivors’ descendants.

Rising frustration

From December 1, Germany began operating new arbitration courts that Berlin describes as long overdue progress.

Yet investigators and lawyers quoted by The Mirror argue the tribunals are stacked with procedural hurdles that will make justice more elusive.

Families say the standards required to file a claim have become so strict that some Jewish heirs may not even qualify.

Also read

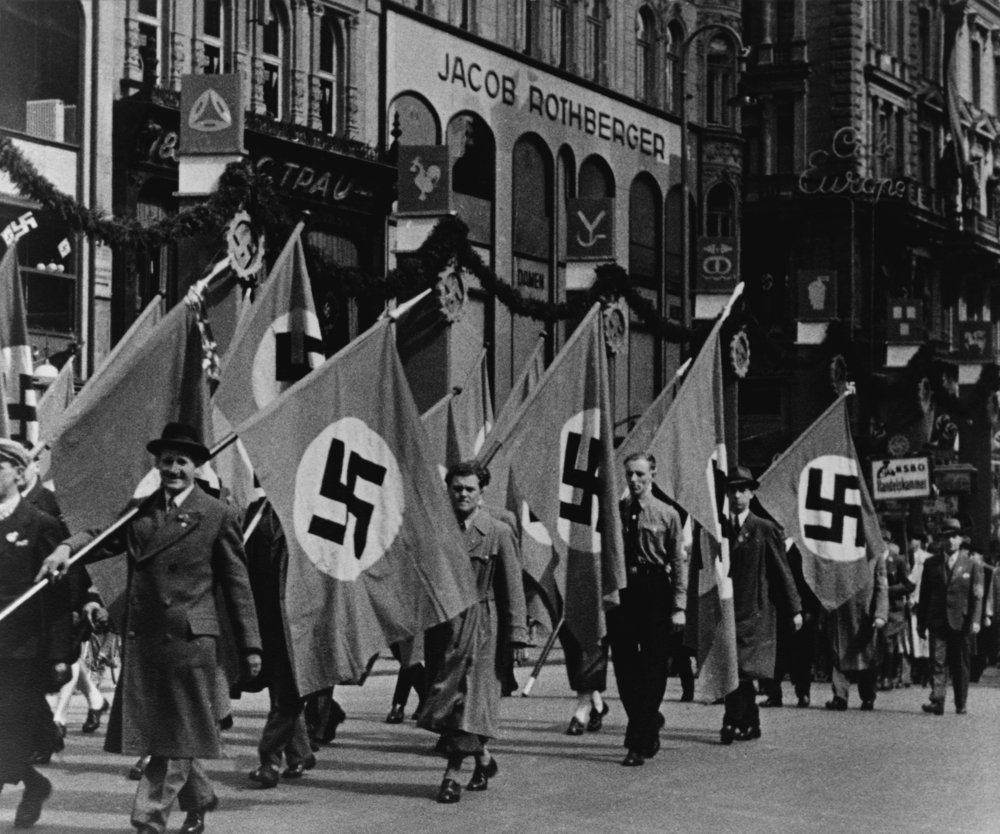

More than 80 years after the end of the Second World War, thousands remain in search of artworks taken under forced sales, extortion or open theft.

Art investigator Willi Korte told The Mirror that the new structure “creates the impression that the procedure is intended to make things more difficult for the claimants. In whose favour? In favour of the museums.”

Burdens on victims

Restitution lawyer Olaf Ossmann said the new framework “forces the persecuted person to prove that there is a direct connection between his persecution and a forced sale.”

This shift places the evidentiary burden on families, despite the fact many records were destroyed during the war or lost across generations.

Another restitution lawyer, Anja Anders, speaking to Germany’s public broadcaster Rundfunk Berlin Brandenburg, warned the new requirements could bar people with incomplete documentation.

Also read

She said: “This will lead one or another partial heir to say: ‘We cannot go to the arbitration court at all, because we are missing another heir.’”

A legacy of stalled cases

Germany estimates that around 600,000 artworks were lost due to Nazi persecution.

Yet since the 1998 Washington Principles were adopted, museums have returned only 7,738 cultural objects and 27,550 books.

The outgoing advisory commission completed just 26 cases in 22 years, largely because institutions had the right to refuse participation.

That opt-out helped museums avoid scrutiny for years.

Also read

The Mirror reports that Bavaria refused to hold a hearing for more than a decade in the long-running dispute over Picasso’s Madame Soler, a painting once owned by Jewish banker Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy.

Only after the rule changes came into force did the state welcome arbitration, a shift critics say reveals who benefits from the new structure.

Who gains from the reform

The introduction of the new tribunals is presented as a way to speed up claims, but experts fear the measures could reduce the number of cases that even reach the table.

With higher thresholds and increased documentation required, the reform may function less as a path to restitution and more as a protective shield for major collections.

Culture minister Wolfram Weimer, speaking through a government statement, maintains the tribunal will bring “new movement.”

Also read

However, lawyers argue the movement appears to be in only one direction, with museums gaining leverage while families face even more obstacles.

The human cost

Behind the legal battles are families who have been waiting generations for a chance to reclaim what was taken.

Many say the new rules extinguish what little hope remained for recovering art stolen under persecution.

Visitors continue to view paintings in German galleries whose original owners were expelled, exiled or killed during the Nazi era.

Sources: The Mirror.