Together, the data reveals a “perfect storm” of climate and social shifts leading up to the outbreak.

Others are reading now

New research suggests that one of history’s deadliest pandemics, the Black Death, may have been sparked by a volcanic eruption.

The plague killed up to half of Europe’s population in the mid-14th century, but scientists now believe the chain of events may have started years earlier with a blast from an unknown volcano.

Scientists connect tree rings, ice cores and old records

To piece together this theory, researchers analyzed tree rings from across Europe, compared them with ice core data from Antarctica and Greenland, and examined medieval documents.

Together, the data reveals a “perfect storm” of climate and social shifts leading up to the outbreak.

A mysterious eruption around 1345 set the stage

According to the study, the eruption occurred around 1345, possibly in the tropics, although the volcano’s exact location remains unknown.

Also read

The ash cloud blocked sunlight across the Mediterranean, lowering temperatures and triggering crop failures over several years.

Grain shortages pushed Italy to the Black Sea

With poor harvests threatening famine and unrest, Italian city-states like Venice and Genoa turned to the Black Sea region for emergency grain imports.

This quick fix may have unintentionally opened the door to something far worse than hunger.

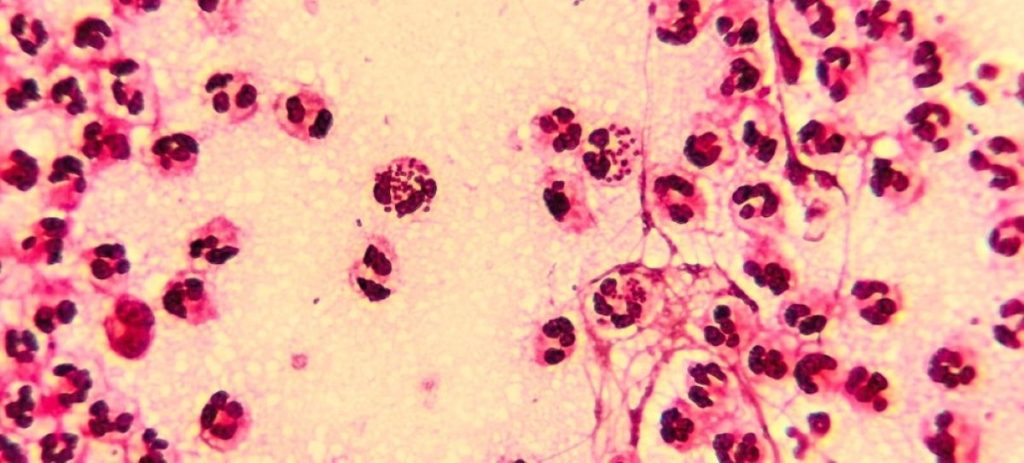

Deadly bacteria hitched a ride with the grain

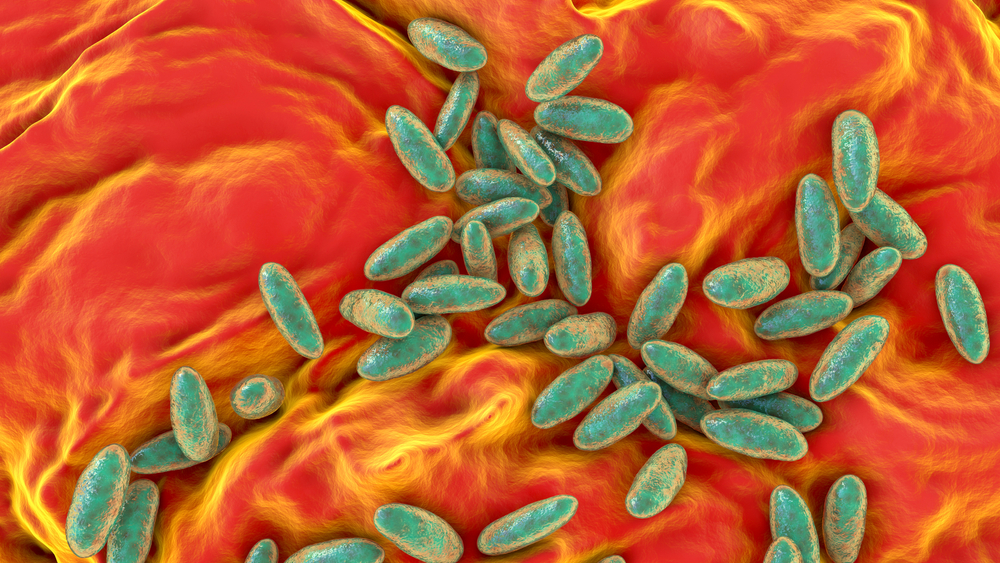

The ships that carried the life-saving grain also transported something deadly: Yersinia pestis, the bacterium behind the plague.

It was likely picked up from wild rodent populations in Central Asia and transported via rat fleas clinging to the grain stores.

Also read

Fleas, grain dust, and an invisible killer

“Rat fleas are drawn to grain and can survive for months on grain dust,” said historian Martin Bauch, one of the study’s coauthors.

This allowed the infected fleas to endure long sea voyages. Once ashore, they found new hosts, including humans, in port cities.

From famine to pandemic in just a few years

The Black Death officially began in 1347, killing at least 25 million people in just four years.

It hit a world still reeling from poor harvests and economic instability, making its impact even more devastating. In some areas, over half the population died.

Tree rings reveal a sudden climate shift

Coauthor Ulf Büntgen studied thousands of tree ring samples to confirm a drop in temperature around 1345–1346.

Also read

Trees grew more slowly during these years, suggesting colder-than-normal conditions that match the timeline of the proposed volcanic eruption.

Ice core data backs up the eruption theory

Further support came from ancient ice samples, which contained spikes of sulfur, chemical fingerprints of volcanic eruptions.

These eruptions are known to cool global temperatures in following summers, helping explain the widespread crop failures.

Why some cities escaped the worst

Not all of Europe suffered equally. Cities like Rome and Milan were less affected, possibly because they relied on local grain supplies and avoided risky imports.

This regional difference supports the idea that grain routes played a crucial role in plague transmission.

Also read

A domino effect of natural and human forces

“This pandemic wouldn’t have happened without a chain of events,” Büntgen said.

The study highlights how climate, trade, and disease dynamics worked together in ways historians and scientists are only beginning to understand.

Historians praise the study’s big-picture view

Experts not involved in the research say it makes an important contribution to our understanding of historical pandemics.

By showing how nature and society interacted, it adds depth to existing theories about how the Black Death spread so quickly and widely.

Lessons for today: climate and disease are linked

The study not only sheds light on the past but offers insights for the future. “Understanding how humans, animals and the environment interact is vital for both history and pandemic preparedness,” said historian Alex Brown.

Also read

The echoes of the Black Death still matter today.