A nuclear meltdown is visible – but what if the killer is invisible?

Others are reading now

On a chilly Monday in early April 1979, residents of the Soviet industrial city of Sverdlovsk—now known as Yekaterinburg—went about their daily routines.

Factory workers clocked in, children went to school, and livestock grazed in nearby fields.

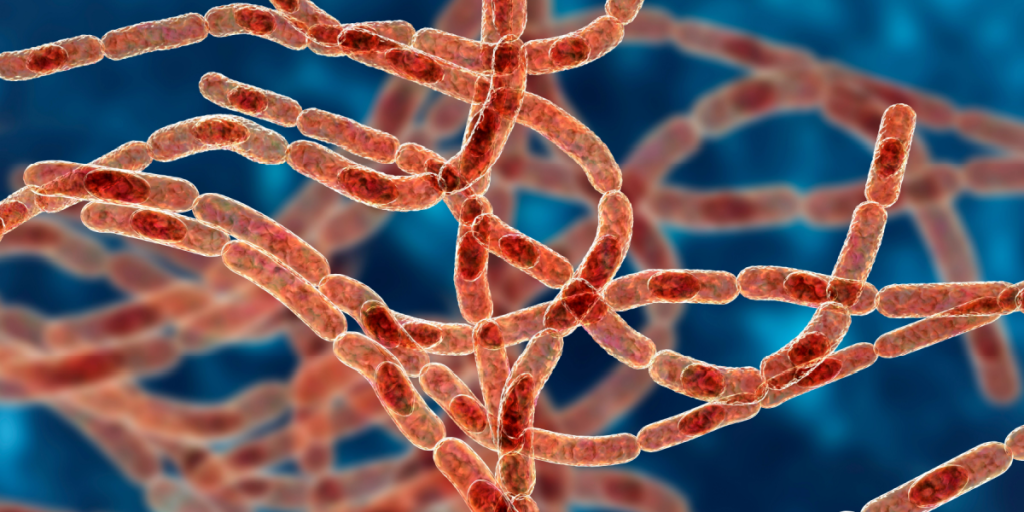

What no one could see was an invisible plume drifting through the air: microscopic spores of Bacillus anthracis, the bacterium that causes anthrax. Within days, people began falling gravely ill. Within weeks, many were dead.

This incident would become one of the most notorious biological accidents of the 20th century.

A deadly release

The outbreak began on April 2, 1979, when spores escaped from a top-secret Soviet military microbiology facility known as Compound 19 on the city’s southern edge.

Also read

The cause: a faulty or missing air filter on an exhaust system, allowing dry anthrax spores—intended for weapons research—to vent into the open air.

Carried by the wind in a narrow plume, the spores spread several kilometers downwind. Anyone outdoors along that path—factory workers, commuters, farmers—risked inhaling them.

Most of the recorded infections were inhalational anthrax, the rarest and deadliest form of the disease, which attacks the lungs and has a very high fatality rate if untreated.

Official figures cite at least 68 deaths, though some estimates, including Soviet and Western data, suggest the toll may have been higher. Livestock along the same wind corridor also died, underscoring the scale of the contamination.

The cover story

From the outset, Soviet authorities worked to control the narrative. Rather than admit a laboratory accident, officials blamed the outbreak on contaminated meat from sick animals sold on local markets. Under this explanation, people became ill after eating infected meat or through cuts and abrasions during butchering.

Also read

This version was repeated in state media and even in international forums. Meanwhile, doctors were instructed to classify many of the cases as “pneumonia” or other non-anthrax diagnoses. Independent access to medical records and affected areas was tightly restricted, hampering international inquiry.

Cold War accusations and scientific investigation

Western intelligence and scientific communities were skeptical of the Soviet narrative almost immediately.

Wind data, illness patterns, and the narrow alignment of victims’ locations suggested an airborne release rather than foodborne transmission—a point highlighted in epidemiological studies that later mapped victims’ homes along a straight downwind line from the facility.

For years, political tensions meant the truth remained obscured. The United States repeatedly accused the USSR of violating the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention by secretly operating offensive biological research and production.

The truth emerges

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, greater transparency became possible.

Also read

In 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin acknowledged that the outbreak resulted from a military facility accident, overturning decades of official denial.

Around the same time, a team of Western scientists led by Harvard biologist Matthew Meselson conducted on-site research that confirmed a plume of aerosolized anthrax had been released from the compound.

Their work, published in major scientific journals, used epidemiology, meteorology, and first-hand accounts to reconstruct the outbreak, conclusively showing that most victims fell ill because they were downwind of the facility—something incompatible with foodborne transmission.

Lasting lessons

The Sverdlovsk anthrax leak remains a stark reminder of the risks inherent in biological research, especially when conducted under secrecy. It highlights how laboratory accidents can have devastating public health consequences, and how political interests can delay the truth. Sverdlovsk is often cited in discussions of biosecurity, laboratory safety, and the challenges of verification in international arms control.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of the tragedy is how ordinary life intersected with extraordinary danger: people didn’t have to break any rules or handle dangerous pathogens to be exposed.

Also read

They simply happened to be downwind on the wrong day.

Sources: Biohazard (book), Stalin’s Secret Weapon (book), The Soviet Biological Weapons Program (book), Science vol. 266, Washington Post, PBS